Japan, the "carry trade", and the economies of Latin America.

- blog de gramirez

- 1468 lecturas

Carry trade and triple arbitrage impact emerging countries due to the difference in interest rates. The interest rate differential between developed and emerging countries such as Mexico, Brazil and Colombia has increased the flow of capital into the financial markets of these countries, which provides more liquidity and public financing. However, it increases the vulnerability of emerging economies to global volatility, as in the case of Japan in August 2024. This article will examine how the Bank of Japan's (BoJ) interest rate hike affected exchange rates in these countries.

Since July 2024, the BoJ has been debating a possible interest rate hike, which triggered a gradual appreciation of its exchange rate. Following confirmation of the rate hike from 0.05% to 0.25%, the Yen appreciated 1.66% on August 5th, triggering a shutdown of carry trades. International traders took advantage of the low rates. They used the Yen as a funding currency for investments in higher-yielding assets in other parts of the world, including Latin America. The rate hike resulted in a knock-on effect on emerging economies such as Mexico, Brazil and Colombia, which experienced capital outflows and pressure on their exchange rates.

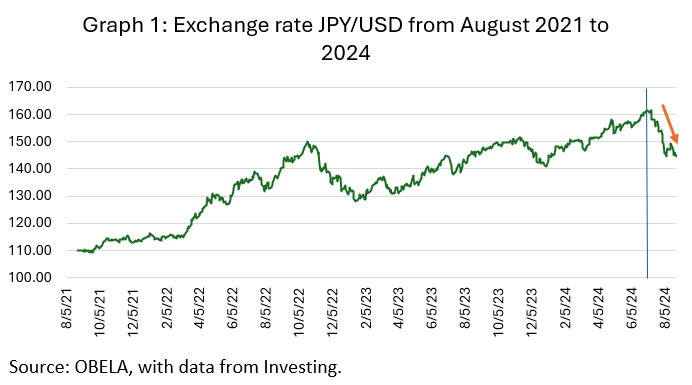

In March 2024, the Yen depreciated by 1.15% due to the first rate hike from -0.10% to 0.05%, and the BoJ left behind eight years of negative rates with no major impact on LA. The rate hike continued and, on August 5th, moved to 0.25%, a total change of 0.30% in three months. As a result, the Yen appreciated 1.66% (see Graph 1), and triggered a closing of carry trades.

Carry trade is a financial strategy where investors borrow in a currency with a low interest rate (such as the Yen) to invest in financial assets in a higher currency. On the other hand, "Triple Arbitrage" is an economic practice where investors seek to maximise profits and decrease risk by exploiting price differentials in three markets: foreign exchange, interest rate and derivatives. This speculative practice appreciates the currencies of economies with high interest rates, such as Brazil, Mexico and Colombia, which makes imports cheaper and exports more expensive and generates exchange rate volatility.

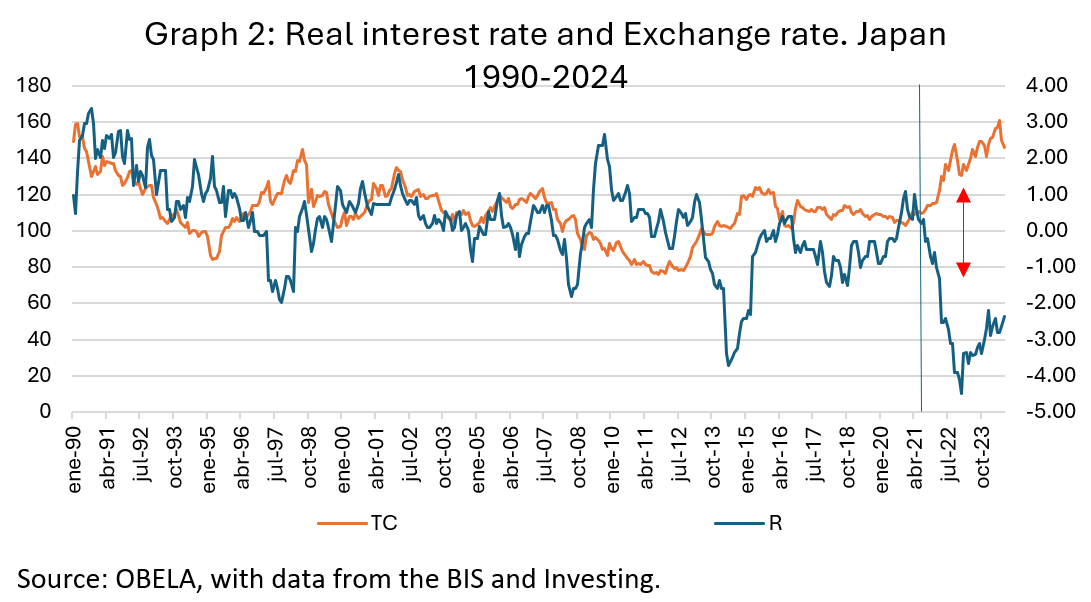

Figure 2 illustrates the behaviour of the real interest rate and the Yen from 1990 to 2024. After the speculative bubble's collapse in the late 1980s, the Asian country entered a three-decade period of stagnation and deflation. BoJ reduced nominal interest rates to zero since the 1990s to stimulate the economy. Despite this, deflation remained, and the real interest rate was positive, limiting demand and investment. A depreciation of the exchange rate was due, given the low nominal rates, but the Yen kept appreciating.

In contrast, a yen depreciation was observed in 1998, attributed to the Asian financial crisis and the Japanese recession, when the BoJ had to bail out overexposed Japanese banks in Asia. In 2016, the Bank of Japan introduced negative interest rates, an unconventional measure implemented after two and a half decades of deflation. The policy meant to encourage consumption or charge interest on bank deposits. The measures allowed the country to make its exports cheaper, increase its competitiveness and lower the financing costs of the state, which paid less interest on its debt. It encouraged international investors to borrow Yen cheaply to invest in higher-yielding assets in emerging markets. Finally, in 2024, the Yen appreciated as interest rates rose in response to emerging inflation and the recovery of other economies.

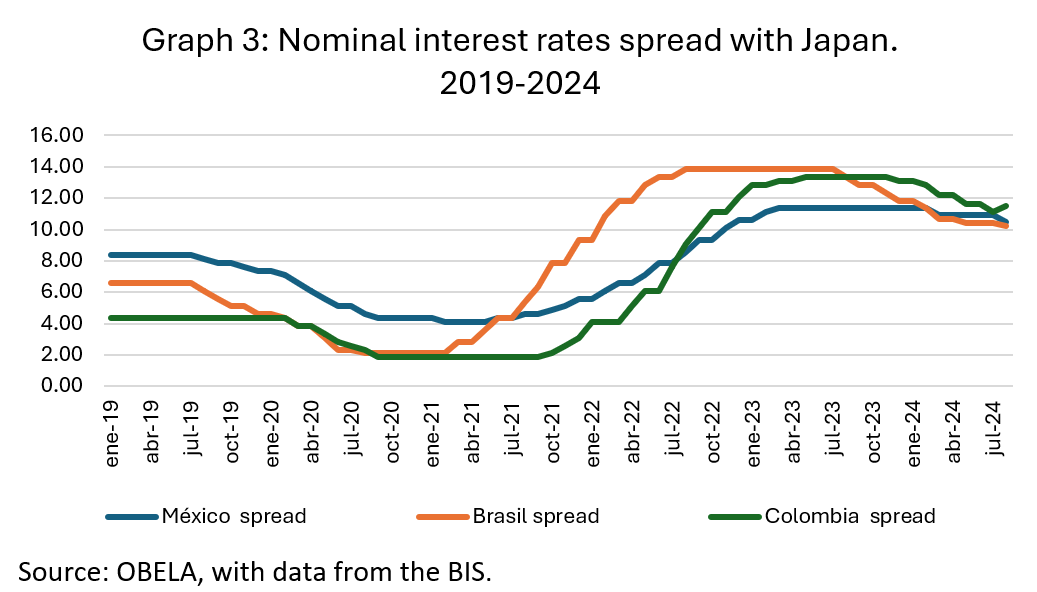

Graph 3 shows how the differential between the nominal interest rates of Mexico, Brazil, Colombia and Japan grew from 2021 onwards. The differential grew first for Brazil, then Mexico, and finally Colombia, which showed its attractiveness to international investors. The spread has allowed yields of up to 10.25% in Brazil, 10.50% in Mexico and 11.50% in Colombia through "Carry Trade".

As Latin America attracts large amounts of foreign capital, the flow of investment strengthens the exchange rate, provides liquidity to emerging financial markets, and increases international reserves or appreciation of emerging currencies. Currency appreciation strengthens confidence in local currencies and can reduce imported inflation, lower the cost of imported goods and thus increase purchasing power. These are the potential benefits of carry trades that can be optimistically viewed.

Despite the short-term benefits, carry trades can generate exchange rate volatility. Since these investments work on interest rate differentials, when conditions change (as with the rate hike in Japan) such capital can be rapidly withdrawn with a depreciating effect on the local currency, injecting inflation and destabilising financial markets. If, on entry, it generates an exchange rate appreciation, on exit, it can produce an exchange rate crisis and inject inflation and economic stagnation. It's crucial to be aware of these potential risks.

The experiences of Chile and Malaysia in the 1990s show how it is possible to reduce exposure to the dangers inherent in carry trade and triple arbitrage. In the early 1990s, Chile faced a massive inflow of short- and medium-term capital flows, attracted by high local interest rates. This scenario exposed the country to the risks above. In order to mitigate vulnerability, in 1991 the Central Bank of Chile introduced a measure known as "encaje no remunerado" or "tax on capital flows".

The reserve requirement mechanism obliged foreign investors to keep 30% of their capital at the central bank for one year without receiving interest to discourage speculation. By increasing the costs of rapid capital inflows, it sought to reduce exchange rate volatility and protect the economy from overvaluation of the peso and possible capital flight. According to Gregorio, Edwards and Valdés (1998), the reserve requirement allowed a change in the composition of capital flows, which increased the proportion of long-term investments to the detriment of short-term ones. As a result, the economy stabilised, and volatility was reduced.

In the case of Malaysia in 1998, at the height of the Asian financial crisis, Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM) implemented strict capital controls to curb the massive outflow of funds and stabilise its economy. The government of Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad opted to keep the exchange rate fixed and impose restrictions so that foreign investors could not withdraw their capital for a year.

Unlike other countries that followed international recommendations for liberalisation, Malaysia and Chile opted for another approach to shield themselves from external volatility, which proved successful. As the situation improved, the countries gradually lifted these restrictions. Malaysia in 2005 allowed managed floating of its currency, marking the end of the most severe controls. Their success stories can inspire hope for effective solutions.

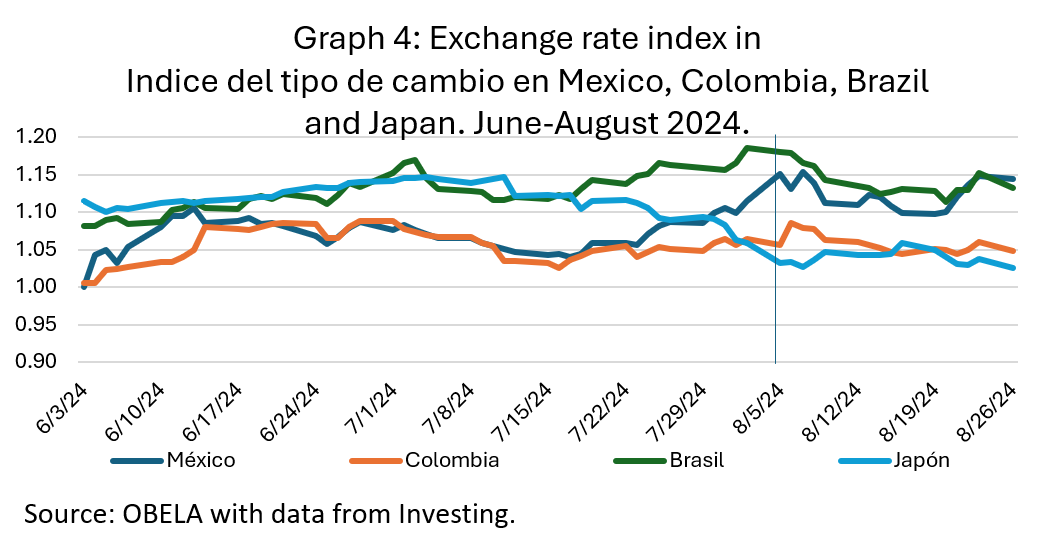

Graph 4 shows that the Mexican peso and the Japanese Yen follow an inverse trend, while there is no clear correlation between the Brazilian real and the Colombian peso, which does not mean there are no Carry Trade dangers. With the narrowing of the interest rate differential, the Mexican peso depreciated by 1.20%. When the Yen depreciates, the peso tends to appreciate, and vice versa, suggesting that carry trade flows influence the Mexican exchange rate. In contrast, the relationship with Brazil and Colombia is less clear, indicating a lesser influence of flows from Japan.

On September 2nd 2024, the BoJ anticipated another possible interest rate hike in December 2024, which is unlikely due to the impact on the yen/dollar price. On the other hand, Colombia and Mexico are countries characterised by following the monetary policies of the FED, which announced an interest rate cut in September. Analysts assume that both central banks will lower their rates, which could result in a yield reduction in carry trade transactions and capital outflows. It may impact both exchange rates.

Galipolo, director of monetary policy at the Central Bank of Brazil (BCB), suggested on August 12th 2024, a possible interest rate hike to meet its 3% inflation target. The potential rate increase could encourage carry trade operations towards Brazil. At the same time, Mexico and Colombia could see a decrease in their capital flows and a depreciation of their currencies.

To conclude, the carry trade and triple arbitrage in countries such as Mexico, Brazil and Colombia generate greater liquidity and expose economies to high exchange rate volatility due to the inflow and outflow of speculative capital. The increase in the BoJ's interest rates strengthened the Yen, which reduced the "carry trade" and provoked depreciation in some emerging currencies and a shock in the stock markets of some countries. A rate cut in these economies could lead to lower yields and negative capital flows, negatively affecting their currencies. Latin American countries could mitigate these risks by following the lessons of Chile or Malaysia and adopting policies that promote financial stability.