What happened in 2021

- blog de anegrete

- 3739 lecturas

The global economic rebound was the prominent feature of 2021. Anticipated as strong rebounds, they turned out to be less intense for some than for others. Governments that injected money into public investment improved their recovery faster than those that did not. In this, Europe recovered, the United States likewise. Some Latin America managed to rebound to 2019 levels, such as Chile. Others are close, such as Colombia and Peru, while others see the return to the 2019 level still distant. Asian countries on their side did not fall much and recovered very strongly. China, which had not contracted, saw a rebound to its slowdown of more than 8% growth, the highest in the world.

The recovery trends have marked changes in growth projections. While the projected GDP growth trajectories before the epidemic were moving in one direction, after the economic contractions of 2020, they have changed the curves downwards, while China's remains on the same arc. This change in economic dynamics made China the new global engine, consolidating a feature that has been apparent since the previous decade. Exceptionally, the Pacific Ocean became the new hub of the world economy, led by China and other Asian countries. The raw materials market gears around South America and the final goods market in the United States. China dominates the global value chains from the first rung. The asynchronicity between Chinese and Western production lies behind the rising prices of electronic end goods.

The inflation observed in 2021 in the world has several causes. The first is the lack of concurrence between Chinese companies that give rise to global value chains in the telecommunications, electronics, automotive, aerospace and pharmochemical sectors and western firms. In other words, after having closed all the world's factories for the first time in economic history, they reopened at different paces. Restarting the entire global production apparatus requires that the supply and demand between the factories' be well synchronized. It was not yet the case at the end of 2021, and global production might return to normality by mid-2022.

A second element is the creation of bottlenecks in transporting goods from one continent to another derived from final pent-up demand. As demand for goods resumed, some preferred to start stockpiling things. It has pushed above-average demand for imported final goods, leading to transportation and disembarkation problems. There is a dislocation between previously existing transportation and landing capacity derived from formerly existing markets and the new excess orders, which surprised the transportation firms. There are long queues of ships to land on both sides of the Pacific. In California and China, there is a shortage of containers and trucks, and transport prices at some point rose over 600% compared to the same time the previous year.

A third element is distribution. Derived from the two previous components comes a problem with goods not reaching the final market in the volumes demanded, affecting final price formation. The impact of the 2021 droughts on food prices could repeat in 2022 if it happens again.

Last but not least is the Fed's injection of liquidity into the U.S. stock and commodity markets in March 2020 while maintaining extreme negative interest rates. It has distorted the price of raw materials whose trade, in volume, remains stable, but prices have skyrocketed. The increases in commodity prices have injected increases in the final costs of goods.

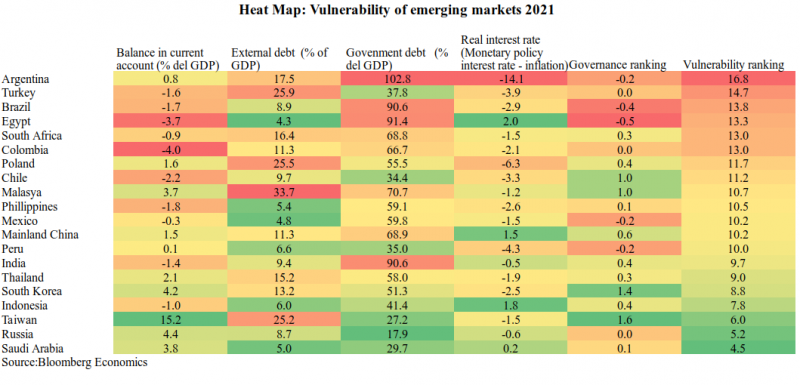

All in all, 2021, after 1981, was the year of the highest inflation in the world, with Brazil, Turkey and the United States leading the way, but followed by all others except Japan and China. The consequence is that central banks worldwide initiated interest rate hikes to contain inflation, so the GDP growth rate in 2022 will be meagre overall. The OECD and IMF projections will again be very optimistic. The question is, how much can interest rates rise. In the U.S., it will have a very high fiscal cost given a debt level of 130% of GDP. In other G7 countries, it is not possible either. The U.S., European countries and Japan all have more than 100% debt to GDP, and rising real levels would strangle them fiscally. So, the recovery of interest rates will still be to fewer negative rates, but by no means to positive rates. Currently, the Fed's short-term rates in the United States are below negative 5%. It was a good year of an economic rebound, but at the cost of high global inflation that central banks will have to deal with in the years ahead.

Many economies are already at pre-pandemic levels of production and employment. Still, another of the gigantic economic leftovers of the crisis is the high indebtedness that plagues developed countries. Fiscal deficits soared in 2020 and 2021 due to combined government support policies to combat Covid-19 and low revenue collection. All this contributed to increased gross debt: according to IMF data, for total developed countries, the ratio rose from 103% to 121% between 2019 and 2021; while in emerging economies, it rose from 54% to 64% in the same years.

Although these stimuli could soften the 2020 downturn and favour the 2021 recovery, it does not mean that they can do anything more. After the remarkable recovery in the second quarter of 2021 for the G7 countries, optimism dropped when the third-quarter data was released. The first-term recovery was rapid due to increases in government deficits and debt. Yet, the following terms spending did not contribute much to sustained economic growth. Instead, what followed was a similar dynamic to the previous 2019 one, but with higher debt, which will have important implications for future government spending and fiscal policy in the G7 countries.