Fed up with market policies in Latin America?

- blog de anegrete

- 3034 lecturas

Throughout the world, the effects of neoliberal policies have exhausted society. As recent demonstrations have shown, societies are tired of sustaining the costs of privatization of public services, flexibilisation of labour legislation, financing of savings and pensions, concentration of wealth, and the pre-eminence of private capital in the allocation of resources. Private interests appropriated economic management and public policy and, with this, took political exercise away from society.

The neoliberal structural reforms correspond to the "Washington Consensus", dictated by the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and the Treasury of the United States. Its policies entered Latin America through coups d'état in Chile in 1973, Argentina in 1976, Uruguay in 1973 and Peru in 1992 and through the conditioning of international financial institutions. It is necessary to add Bolivia, in 1985, under the government of Victor Paz Estenssoro; Mexico, in 1888, with Salinas de Gortari; Brazil, in 1990, with Fernando Collor de Mello and Fernando Henrique Cardoso later. Finally, between 2001 and 2006 with the defenceless governments of Gustavo Noboa (2000-2003) and Lucio Gutiérrez (2003-2005) that ended in the Citizens' Revolution and Rafael Correa and the truncated process. Except in Cuba, Venezuela and Bolivia, since the end of the 1980s, economic policy in Latin America has been based on the market; that is, the principle of non-interventionism in the economy and the logic of fiscal surpluses.

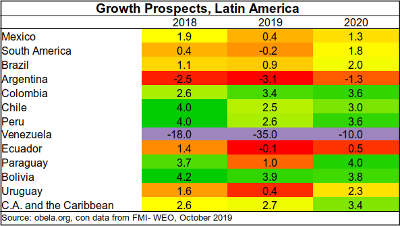

The economic balances are ambiguous, with successive financial crises, high concentration of income and social exclusion at the same time as declining primary export growth, decade by decade since 1990. However, social balances are even worse in terms of privatization of public goods such as education, health, and the deterioration of salaries, the quality of employment and pensions. The October protests in Ecuador, Chile, Haiti and Argentina express a general feeling of fed up with the economic policy model.

In Ecuador, mobilizations followed President Lenin Moreno's announcement of a new Austerity Plan that included a reduction in government spending, a withdrawal of fuel subsidies and a 25% increase in the price of gasoline. Escalating indigenous and urban protests forced the government to leave the capital, Quito, and move to Guayaquil. After twelve days of protests, eight dead and more than 1,300 injured, Moreno's government withdrew its Plan and repealed Decree 883, reversing the increase in fuel prices. It is clear that the return to normality is brief and that the pressure from the IMF to reduce its fiscal deficit will hardly stop there and, therefore, neither will Ecuadorian discontent.

In Chile, demonstrations began with the announcement of a 3% fare increase of the Santiago City subway (from 800 to 830 pesos-from US$1,091 to US$1,132-) in early October 2019. After the first six days of protest and four nights of curfew, President Piñera apologized for the lack of "vision in recognizing the situation in all its magnitude" and announced the cancellation of the subway fare increase and a package of measures for other basic (private) services such as education and health. But the discontent goes even further, as it drags the damages of the 46 years since the 1973 coup and the 29 years of democracy that neither repaired the truth of the crimes of the military regime, and its punished them, nor reversed the constitution written in 1980 by the military government and kept it under the agreement with the parties in the return to democracy. Two weeks after mobilizations, at the time of writing, with at least 20 dead, more than 3,000 detained and countless wounded, and destruction of infrastructure for around 1 billion dollars, President Piñera announced the dismissal of his Cabinet and suspended the APEC and COP 25 conferences that were to take place in Santiago and accepted his political defeat. However, it seems that Chilean society recognizes that it must change its economic regime and even its political regime, agree to a new constitution and Piñera ousted.

Meanwhile, elections were held in Argentina and Uruguay this past October 27. Argentine society expressed its weariness with structural reforms, IMF interventionism and, in general, market policies. The Peronist Alberto Fernandez, seconded by Cristina Fernandez as vice president, was elected without the need for a second round. With this, Argentina seeks to retake the progressive route inaugurated in 2003 with Néstor Kirchner and abandon IMF policies.

In Uruguay in the first round of the presidential vote, after 15 years of progressive economic policies, the Frente Amplio candidates obtained 39.17% of the vote, without the absolute majority to govern in the first round, and the National Party, 28.59%. They are going to a second round where Lacalle, of the National Party (Blanco), son of former President of the Republic Luis Alberto Lacalle, may win. The latter, with Bolsonaro's help, seems to be part of the support to the Uruguayan right. In countertrend, it seems feasible that he beats the Frente Amplio, and reinforces free market policies in the region.